Listen to the speaker read the text, then read it yourself out loud.

The multiple-choice questions at the end of the text will help test your understanding.

The Bible is a remarkable book. It claims to be inspired by God and to accurately record history. I used to doubt the historical accuracy for the beginning chapters of the first book in the Bible – Genesis. This was the account of Adam & Eve, paradise, the forbidden fruit, a tempter, followed by the account of Noah surviving a worldwide flood. I, like most people today, thought these stories were really poetic metaphors.

As I researched this question, I made some fascinating discoveries that made me re-think my beliefs. One discovery lay embedded in Chinese writing. To see this you need to know some background about the Chinese.

Written Chinese started at the beginning of Chinese civilization, about 4200 years ago, some 700 years before Moses wrote the book of Genesis (1500 BC). We all recognize Chinese calligraphy when we see it. What many of us don’t know is that ideograms or Chinese ‘words’ are made from simpler pictures called radicals. It is similar to how English takes simple words (like ‘fire’ and ‘truck’) and combines them into compound words (‘firetruck’). Chinese calligraphy has changed very little in thousands of years. We know this from writing that is found on ancient pottery and bone artifacts. Only in the 20th century with the rule of the Chinese communist party has the script been simplified.

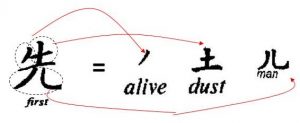

For example, consider the Chinese ideogram for the abstract word ‘first’. It is shown here.

‘First’ is a compound of simpler radicals as shown. You can see how these radicals are all found combined in ‘first’. The meaning of each of the radicals is also shown. What this means is that around 4200 years ago, when the first Chinese scribes were forming the Chinese writing they joined radicals with the meaning of ‘alive’+’dust’+’man’ => ‘first’. But why? What natural connection is there between ‘dust’ and ‘first’? There is none. But notice the creation of the first man in Genesis.

The LORD God formed the man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life and the man became a living being (Genesis 2:17).

The ‘first’ man (Adam) was made alive from dust. But where did the ancient Chinese get this connection 700 years before Moses wrote Genesis? Think about this:

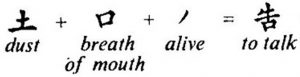

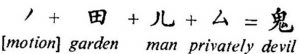

The radicals for ‘dust’ + ‘breath of mouth’ + ‘alive’ are combined to make the ideogram ‘to talk’. But then ‘to talk’ is itself combined with ‘walking’ to form ‘create’.

But what is the natural connection between ‘dust’, ‘breath of mouth’, ‘alive’, ‘walking’ and ‘create’ that would cause the ancient Chinese to make this relationship? This also bears a striking similarity with Genesis 2:17 above.

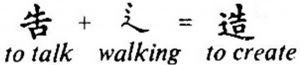

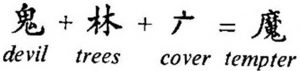

This similarity continues. Notice how ‘devil’ is formed from “man moving secretly in the garden”. What is the natural relationship between gardens and devils? They have none at all.

Yet the ancient Chinese then built on this by then combining ‘devil’ with ‘two trees’ for ‘tempter’!

So the ‘devil’ under the cover of ‘two trees’ is the ‘tempter’. If I was going to make a natural connection to temptation I might show a sexy woman at a bar, or a tempting sin. But why two trees? What does ‘gardens’ and ‘trees’ have to do with ‘devils’ and ‘tempters’? Compare now with the Genesis account:

The LORD God had planted a garden in the east… in the middle of the garden were the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Genesis 2:8-9)

Now the serpent was more crafty… he said to the woman, “Did God really say …” (Genesis 3:1)

To ‘desire’ or ‘covet’ is again connected with a ‘woman’ and ‘two trees’. Why not relate ‘desire’ in a sexual sense with ‘woman’? That would be a natural relation. But the Chinese did not do so.

The Genesis account does show a relation between ‘covet’, ‘two trees’ and ‘woman’.

When the woman saw that the fruit of the tree was good for food and pleasing to the eye, and also desirable for gaining wisdom she took some and ate it. She also gave some to her husband (Genesis 3:6)

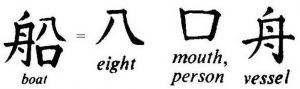

Consider another remarkable example. The Chinese ideogram for ‘big boat’ is shown below and the radicals that construct this are also shown:

They are ‘eight’ ‘people’ in a ‘vessel’. If I was going to represent a big boat why not have 3000 people in a vessel. Why eight? Interestingly, in the Genesis account of the flood there are eight people in Noah’s Ark (Noah, his three sons and their four wives).

The parallels between the early Genesis and Chinese writing are remarkable. One might even think the Chinese read Genesis and borrowed from it, but the origin of their language is 700 years before Moses. Is it coincidence? But why so many ‘coincidences’? Why are there no such parallels with the Chinese for the later Genesis stories of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob?

But suppose Genesis is recording real historical events. Then the Chinese – as a race and language group – originate at Babel (Genesis 11) as all other ancient language/racial groups. The Babel account tells how the children of Noah had their languages confused by God so that they could not understand each other. This resulted in their migration out from Mesopotamia, and it restricted inter-marriage to within their language. The Chinese were one of these peoples dispersing from Babel. At that time the Genesis Creation/Flood accounts were their recent history. So when they developed writing for abstract concepts like ‘covet’, ‘tempter’ etc. they took from accounts that were well understood in their history. Similarly for the development of nouns – like ‘big boat’ they would take from the extraordinary accounts that they remembered.

Thus the accounts of Creation and the Flood were embedded into their language from the beginning of their civilization. As the centuries passed they forgot the original reason, as so often happens. Is it the case then that the Genesis account recorded real historical events, not just poetic metaphors?

Chinese Sacrifices

The Chinese had one of the longest lasting ceremonial traditions that has ever been conducted on earth. From the start of the Chinese civilization (about 2200 BC), the Chinese emperor on the winter solstice always sacrificed a bull to Shang-Ti (‘Emperor in Heaven’, i.e. God). This ceremony continued through all the Chinese dynasties. In fact it was only stopped in 1911 when general Sun Yat-sen overthrew the Qing dynasty. This bull sacrifice was conducted annually in the ‘Temple of Heaven’, which is now a tourist attraction in Beijing. So for over 4000 years a bull was sacrificed every year by the Chinese emperor to the Heavenly Emperor. Why? Long ago, Confucius (551-479 BC) asked this very question. He said:

“He who understands the ceremonies of the sacrifices to Heaven and Earth… would find the government of a kingdom as easy as to look into his palm!”

What Confucius said was that anyone who could unlock that mystery of the sacrifice would be wise enough to rule the kingdom. So between 2200 BC when the Bull Sacrifice began, to the time of Confucius (500 BC) the meaning of the sacrifice had been lost to the Chinese – even though they continued the annual sacrifice another 2400 years to 1911 AD.

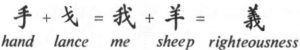

Perhaps, if the meaning of their calligraphy had not been lost Confucius could have found an answer to his question. Consider the radicals used to construct the word for ‘righteousness’.

Righteousness is a compound of ‘sheep’ on top of ‘me’. And ‘me’ is a compound of ‘hand’ and ‘lance’ or ‘dagger’. It gives the idea that my hand will kill the lamb and result in righteousness. The sacrifice or death of the lamb in my place gives me righteousness.

Genesis has many animal sacrifices long before Moses started the Jewish sacrifice system. For example, Abel (Adam’s son) and Noah offer sacrifices (Genesis 4:4 & 8:20). It seems that the earliest people understood that animal sacrifices were symbols of a substitute death that was needed for righteousness. One of Jesus’ titles was ‘lamb of God’ (John 1:29). His death was the real sacrifice that gives righteousness. All animal sacrifices – including the ancient Chinese Border Sacrifices – were only pictures of his sacrifice. This is what Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac pointed to, as well as Moses’ Passover sacrifice. The ancient Chinese seemed to have started with this understanding long before Abraham or Moses lived, though they had forgotten it by Confucius’ day.

This means that the sacrifice and death of Jesus for righteousness was understood from the dawn of human history. Jesus’ life, death and resurrection was a Divine plan reinforced with signs so people could know it from the beginning of time.

This goes against our instincts. We think that righteousness is based either on mercy of God or on our merits. In other words, many think no payment is required for sin since God is solely merciful and not Holy. Others think that some payment is required, but that we can make the payment by the good things we do. So we try to be good or religious and we hope it will all work out. This is contrasted by the Gospel that says:

But now a righteousness from God, apart from Law, has been made known… This righteousness comes through faith in Jesus Christ to all who believe (Romans 3:21-22)

Perhaps the ancients were aware of something that we are in danger of forgetting.

Bibliography

- The Discovery of Genesis. C.H. Kang & Ethel Nelson. 1979

- Genesis and the Mystery Confucius Couldn’t Solve. Ethel Nelson & Richard Broadberry. 1994

Common Expressions

Below you can find common English expressions that are used when talking about learning a foreign language.

“Make someone look bad” – To do something that makes the people who are with you feel ashamed.

Example: “The kid was throwing a tantrum and making her parents look bad.”

“Learn something the hard way” – To learn something through personal experience, especially when it is difficult or painful.

Example: “You open that door by pulling. I had to learn that the hard way after hitting my head because I tried to push it at first.”